Social enterprise Vs.

anti-social enterprise?

Recently there has been a flurry of news and a growing acceptance from the public that the brand of capitalism that puts the shareholders’ interest above all else, is broken. Indeed, the FT recently reported that City Fund managers are calling for a radical rethink and an end to the constant obsession with economic growth.

Recently there has been a flurry of news and a growing acceptance from the public that the brand of capitalism that puts the shareholders’ interest above all else, is broken. Indeed, the FT recently reported that City Fund managers are calling for a radical rethink and an end to the constant obsession with economic growth.

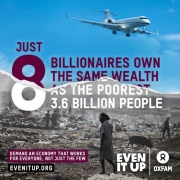

We are in the middle of societal and environmental disaster, made evident by huge levels of income inequality and poverty (last year Oxfam reported that the world’s richest 1% bagged 82% of the world’s wealth), as well as the Climate Emergency.

It was also interesting to see the recent announcement by the Labour Party regarding their intention to revise the Companies Act to “take on the excesses of the shareholder model and lay some of the foundations of a stakeholder economy”, should they win a majority at the upcoming election.

Last week a shocking new report from the TUC and High Pay Centre highlighted just how broken the ‘shareholder first’ model really is. The evidence set out in the report shows how, in the corporate world, delivery to the shareholder has become an obsession.

Even those more enlightened CEOs who have tried to move outside the straightjacket to take into consideration people and planet (e.g. Unilever) have ended up being potentially strong-armed back into the prevailing model by becoming vulnerable to ‘Hostile Sustainability Raiders’ – i.e. hostile takeover organisations that jump in (in order to make quick financial returns) because the share price has dropped due to lower dividends. Short-termism is factored indelibly into the corporate business model.

Figures from our report with @The_TUC out today on how the shareholder-first model contributes to poverty, inequality and climate change.

Read the report here: https://t.co/c9LMylqNRj pic.twitter.com/XuD4twe5FU

— High Pay Centre (@HighPayCentre) November 14, 2019

The evidence of the resulting behaviours leads to stark consequences not only for those working for those companies, but also to their wider stakeholders and communities. The more money that is extracted for shareholders, the less there is for anything else. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) budgets, increases in wages for workers and social and environmental impact come in as the ‘poor relatives’.

The following startling statistics illustrate the reality versus the hype:

- In 2018, BP spent 14 times and Shell 11 times more on their shareholders as they invested in low carbon activity

- Between 2014-18, while FTSE 100 returns to shareholders rose by 56%, the median wage for UK workers increased by just 8.8% (both nominal)

- In 2018, the 4 largest food and drinks companies paid shareholders almost £14 billion – more than they made in net profit (£12.7 billion). To put that into perspective, just a tenth of this shareholder pay-out is enough to raise the wages of 1.9 million agriculture workers around the world to a living wage

- Gender inequality is much higher in FTSE 100 companies (the gender pay gap is double the national average), as cheaper women’s labour helps to support increased shareholder returns

Shareholder primacy is reinforced in the Section 172 of the 2006 Companies Act, which requires company directors to act in the interest of shareholders, and only ‘have regard’ to a wider set of stakeholders. There are no significant examples of a director being held to account for their failure to ‘have regard’ for their wider stakeholders. We are working with Social Value UK and other partners to change this.

Shareholder primacy is reinforced in the Section 172 of the 2006 Companies Act, which requires company directors to act in the interest of shareholders, and only ‘have regard’ to a wider set of stakeholders. There are no significant examples of a director being held to account for their failure to ‘have regard’ for their wider stakeholders. We are working with Social Value UK and other partners to change this.

The How Do Companies Act campaign aims to change accounting behaviour to ensure that accounting practice also takes consideration of social and environmental impact.

Social enterprise (a business model that puts society and the environment before shareholder profit) is part of the solution to this rampant anti-social/environmental trend. We have been saying this for a long time. Rather than shareholder gain being the sole driver, social enterprises focus on the three ‘P’s:

- Purpose – social mission locked in through governance and legal form as well as creating social impact as a central tenet (including environmental objectives and impact)

- Profit – profit and dividends shared by stakeholders for the benefit of the purpose. Check out my colleague Richard’s recent blog for more information on this

- Power – the involvement of and dialogue with stakeholders around decisions making

Social enterprises (that hold the Social Enterprise Mark/Gold Mark) dedicate a majority (at least 51%) of their profits to social and environmental purpose, as well as being dedicated to changing society for the better in the way that they conduct their core business. They therefore compare favourably on many different indicators of social benefit mainly because they are focused on social good:

|

Social Enterprises (Source: State of Social Enterprise 2019) |

FTSE100 (Multiple sources) |

|

| Pay real Living Wage |

76% |

37% |

| CEO to worker pay ratio |

8.4:1 |

145:1 |

| Shareholder profits |

25% |

80% |

| Directors from ethnic minorities |

24% |

2% |

| Female CEOs |

41% |

7% |

Given all of this, it is pretty clear that if we are to change society for the better and to tackle the climate emergency we need to challenge much more radically what it means to be a business. We need to stop teaching and assuming that it’s all about getting financially more wealthy and see wealth in a much wider context – creating a better world for all.

anti-social enterprise?